Blinders on

The year was 2018. SXSW (remember real life conferences?) was in full swing. Panasonic’s Future Life Factory revealed their newest design prototype.

Horse blinders. For people. Attached to a pair of noise-cancelling headphones.

Or, in loftier terms, “WEAR SPACE… a wearable device designed to aid concentration by limiting your senses of sight and hearing, via noise-canceling technology and a partition that controls your field of view.”

Image source. Peak-2018 open office wear.

The design was met with near-universal snark and seen as a nightmarish response to the proliferation of open-plan offices. As Brian Heater questioned in TechCrunch, “At what point do we just give up and admit we’re living in exactly the dystopian nightmare speculative fiction warned us about? It probably ought to be these horse blinders for people, which look like something straight out of a Terry Gilliam movie.”

Were your 2018 coworkers so distracting you’d be willing to wear goofy blinders to cope?

For many people, the problem of coworker or coworker distraction has not disappeared in the work from home era. Without the luxury of a closed home office or a backyard office pod, people have been thrown into working in shared spaces with their partners, roommates, family members, or whoever else is around.

Image source. WFH coworker distraction.

Perhaps those horse blinders are looking more appealing by the day. Personally, I have for years resorted to a functionally equivalent pairing of noise cancelling headphones and a hood-up hoodie, a no-doubt charming look my husband calls my “highly sensitive person uniform.”

Yes, trying to concentrate while sharing space with other people can be overwhelming.

All about the face

We can’t help it. We’re naturally drawn to faces. Even if faces have nothing to do with what we’re doing.

In one study, participants were shown a rapid sequence of letters in different colors and were asked to identify a target (e.g., every green letter). Meanwhile, irrelevant faces were unexpectedly displayed on the screen. Seeing them impaired people’s performance.

The researchers also added a couple of control conditions to check if the effect was specific to faces. In one, they showed people a blank frame in the same locations that faces would appear. In another, they created a “face control” by scrambling the face images that would normally serve as distractors. Neither frames nor the face control images impaired performance the same way.

Image source, annotations added. Faces are particularly distracting.

Another study came to similar conclusions. In that one, people were asked to categorize the orientation of a red letter “T” that appeared in a different orientation every second. During some trials, an irrelevant distractor appeared on the screen and continued for a varied length of time.

In one experiment, there were two types of distractors: pictures of faces and pictures of places. The appearance of both faces and places initially distracted people. However, the effect of places disappeared quickly – after one second. Meanwhile, the distraction from faces dragged out longer – for three seconds.

Image source. Both irrelevant images of faces and places distracted people, but the distraction faded quickly for images of places.

In a second experiment, the researchers tested what would happen if all the distractors were faces. Would people acclimate and be able to tune them out? They found that context matters when it came to the length of distraction. When all the distractors were faces, people were able to disengage from them faster than they would otherwise. However, the distraction didn’t fully disappear – new faces continued to be distracting.

These findings suggest that if faces are all around us, we may end up rapidly cycling through engaging and disengaging attention to them. And in an environment where faces appear unpredictably, they likely hold our attention for even longer.

As an interesting aside, faces don’t even have to be that realistic to distract us. Another study found we can be distracted by the appearance of irrelevant cartoon characters, including Pikachu, Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Spongebob Squarepants, and Spiderman.

Blocking out distractions

How can we minimize the visual distractions that people bring, without getting rid of the people? A reasonable guess would be to block them from our line of sight.

When we anticipate a future need to expend cognitive resources, we seem to pre-allocate those resources. So, if there are distractors in our environment, like faces, we might pre-allocate more resources to monitoring them.

Visually blocking part of the environment might free up resources that would otherwise be allocated for this monitoring and let us put more effort into what we want to be doing.

A study on the effects of visual barriers supported this idea. In the study, people sat alone in an empty, windowless (boring) room and completed experimental tasks. For half of the participants, a visual enclosure (a wooden cubicle) around their desk blocked most of the room from their sight. Half didn’t have a visual enclosure.

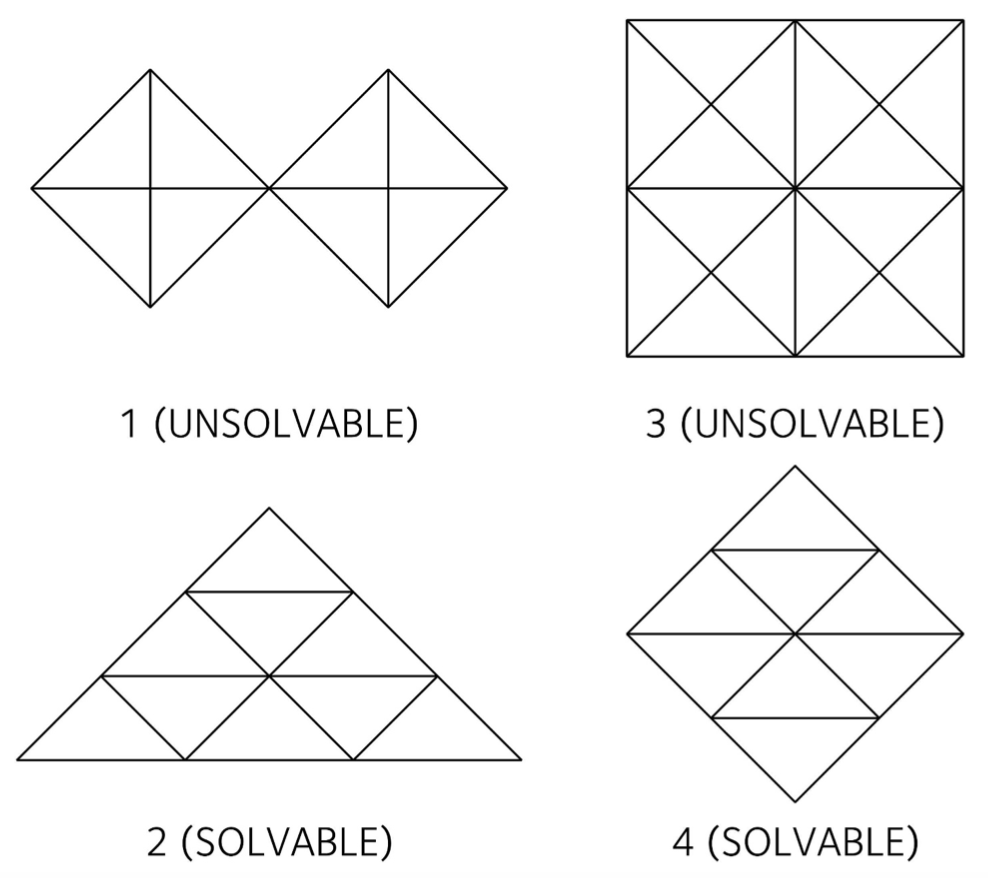

In one task, participants were asked to solve puzzles. But not just any puzzles – some were solvable and some were impossible. People who were surrounded by a visual enclosure showed better perseverance. They made more attempts to solve the impossible puzzles (6+ on average) than those who saw the whole room (4 puzzle attempts on average).

Image source. People surrounded by a visual enclosure made more attempts to solve impossible puzzles.

In another potentially frustrating task, participants had to sort nuts and bolts into bins by moving them one a time with one hand (yep!). People enclosed by the cubicle perceived the effort of the task to be lower.

Better perseverance and lower perceived effort sound pretty good. So do not having to monitor the environment for distractions or glancing over anytime someone working next to you reacts to something they’re reading.

And look, maybe Panasonic knows us better than we know ourselves. They recently released the Komoru, a little cubicle for the living room.

Image source. Bright light, no faces in sight.