Lines, looming, and learning

Jagged lines

People like curves. As we talked about previously, people tend to prefer curvilinear over angular shapes. But I recently came across a paper that found an exception to this pattern. I would not call the methods or results rock-solid, but the study could serve as an interesting launching point for further work.

The study compared how three different groups—children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), neurotypical children, and neurotypical adults—responded to various simple shapes. The key contrast was between the two groups of children. There were some differences in overall reactions. For example, children with ASD started vocalizing once shapes appeared, neurotypical children didn’t. Neurotypical children decreased their body movements once shapes appeared, children with ASD didn’t.

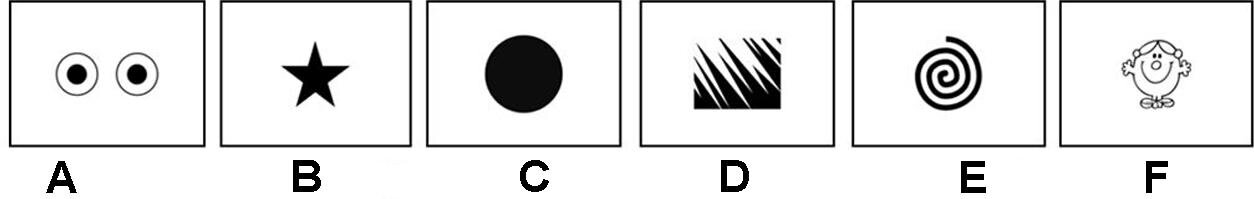

But an interesting difference was in the children’s reactions to the individual shapes. The kids rated how each shape made them feel—negative, neutral, or positive—using a smiley scale. The neurotypical children felt the most positive viewing a spiral, a curvilinear shape. Meanwhile, children with ASD felt the most positive viewing a shape with jagged edges, an angular shape. The children varied in age from 4 to 15, but there were no effects of age, suggesting that the differences between the groups might be relatively stable.

Image source. Shapes used in the study. Spiral (E) and shape with jagged edges (D)

While these are just preliminary findings, perhaps people or children with ASD might be one group for whom angular shapes are more positive than curves.

This study also had an interesting side-finding for adults. The researchers showed adults both static and looming (i.e., coming toward them) versions of each shape. The adults didn’t feel good about the looming, not at all. They liked the static shapes more.

To minimize the number of comparisons made between groups of children, all the children saw looming versions of the shapes. But this brings us to another finding about children and looming.

Looming

A study found that, perhaps counter-intuitively, vehicles that travel faster loom less in our perceptual field than vehicles that travel slower. And sensitivity to looming develops over childhood, with even 10-11 year olds less able to pick up on looming motion than adults.

So? So, that’s super dangerous! It means that kids are unlikely to notice when fast-moving cars are coming at them.

Here’s the take-home: “when children do not fixate directly on approaching vehicles, or are in motion themselves, they cannot reliably detect the approach of vehicles that are 5 s away and traveling at speeds of 30 mph or higher.”

Holy moly!

Pedestrian injury is one of the leading causes of child death in much of the world. And programs on pedestrian safety stress that kids should be reminded to pay attention. Sure, that is great, but it doesn’t address the fundamental problem that even if they do pay attention, they’re not that good at seeing the speed of oncoming cars.

Sometimes you can out-behavior an environment, but this seems like a pretty clear case for an environmental intervention—pedestrian zones around schools, playgrounds, and anywhere else kids are crossing streets.

(It may not surprise you that that I’m my family’s chief safety officer).

Simple classrooms

Speaking of kids and space, I recently came across an ArchDaily article summarizing how the Montessori method could be applied to the design of children’s spaces. The environment is a big deal in Montessori, forming one of its three pillars: “The child, the conscious adult, and the prepared environment should always be together, connected.”

Some of the Montessori-recommended features in kid spaces include simplicity, minimalism, and organization. Basically, keeping things simple, simple, simple.

And, as it turns out, there’s research on that idea.

Image source. Keeping things simple in the classroom.

A study on classroom environments for young children found that simple, minimally decorated classrooms led to better learning. Here’s how the study worked.

Kindergarten students went into a lab classroom for six science lessons on new topics (e.g., plate tectonics, volcanoes, and bugs) taught by a new, trained teacher who didn’t know about the hypotheses of the study. Each lesson took place on a different day.

The key variable in the study was how heavily decorated the classroom was. For half of the lessons, the classroom was heavily decorated with the kind of visual distractions typical of normal primary classrooms (science posters, maps, and even the students’ own artwork brought in by their normal teacher). For the other half of the lessons, the classroom was sparse – there was nothing on the walls.

Image source. Study classrooms.

After each lesson, the researchers gave students small assessments to measure their learning, which were compared to pretest assessments given before lessons in the experimental classrooms began.

During each lesson, the researchers also recorded and coded when students were on-task and off-task and what they were paying attention to if off-task (to themselves, to peers, to the environment, or other).

When the classroom was heavily decorated, students were more distracted–they spent more time off-task. And when they weren’t paying attention to the lesson, they were most commonly paying attention to the surrounding environment. On the other hand, when the classroom was sparse, students were less distracted and off-task attention was mostly focused on the other students – the environment shrank as a source of distraction.

Learning was affected by classroom decoration: students showed smaller learning gains in the heavily decorated classroom.

Learning is hard! And kids are sensitive to the visual environment, so keeping classrooms simple might help them stay on-task.

Cute benefits

You know what else kids are? Cute. Especially babies.

There’s a long-standing idea that cute babies looking like cute babies is one thing that gets us to be more careful and protective of them.

A study tested this cuteness idea directly by seeing whether cute animals also elicit careful behavior. Here’s how the researchers explained their logic: “Because caring for a small, delicate child requires one to act with great care, we reasoned that cuteness cues might stimulate increased attention to, and control of, motor behavior.” Yes.

The study design was pretty fantastic. Participants saw a slideshow of either very cute animals (puppies or kittens), or less cute animals (full-grown dogs and cats, and some lions and tigers in a second experiment). To test behavioral carefulness, the researchers used a classic… game. Operation, which requires a true feat of dexterity to pick out tiny plastic pieces from an ailing plastic “patient” using tiny tweezers.

The researchers also measured participants’ physiological reactions while viewing the slide show and the feelings they experienced.

People were, indeed, better at Operation after viewing cute animal pictures. There was also a trend of women being more responsive to cuteness than men.

One experiment included only women (and a slightly-less-controlled set of images). There were some additional findings. Women’s heart rate increased more seeing the cute vs. somewhat cute animals, and they experienced greater feelings of tenderness seeing the cute animals. In addition, the more tender women felt when viewing the animals, the better their performance on Operation. This suggested that their more careful behavior was activated by feeling tender after viewing cute animals.

Image source. Cute knife switch for the kitch.

I’ll be on the lookout for a replication of this cute-animals effect with real surgeons. Meanwhile, an at-home replication could test whether cute animal kitchen gear improves fine-motor knife skills.