Putting numbers on experience

I think many of us have had the following experience in the pre-COVID world.

You land at an airport (the pre-reno LaGuardia comes to mind) with bathrooms that are few and far between. The plane empties and the post-flight crowd immediately re-forms into bathrooms lines. It’s an instinct as strong as geese assembling into a V formation when they fly.

In line, people wait to use the too-small, poorly maintained facilities. The sink area is crowded with suitcases underfoot and people who feel the urgent need to brush their teeth. Right now.

You finally make it out, freeing your suitcase from the throng and dragging it toward the bathroom exit. Just as you’re about to leave, you see it. A grimacing red smiley with sad eyes. It seems to know exactly what you’re feeling.

Do you push its little face to indicate that “Yes, buddy, I hear you, this bathroom is too small, gross, and generally unpleasant”? Hell yah, you push it.

And with that, another data point streams into the servers of the Finnish company HappyOrNot.

If you’re interested in the full HappyOrNot origin story, check out David Owen’s 2018 piece in the New Yorker. But here are the highlights.

Once upon a time, the founder and CEO, Heikki Väänänen, was a teenager shopping at an electronics store and couldn’t find any employees to help him buy the computer diskettes he needed. He wanted to share this feedback with someone working at the store chain who might care and make a difference for future customers, but how? “Filling out surveys isn’t something you can always do, so it came to my mind that maybe there could be an easier way to give feedback, and to send the data directly to people who are interested in the results,” he said.

Ten years later, Väänänen told his idea to a coworker who thought it was so obvious and simple that someone must’ve done it already. When they realized no one had, the two quit their day jobs to develop the now-ubiquitous free-standing battery-powered feedback terminals. They installed their first terminal at the end of 2009, and, by 2019, the company had 30,000 terminals installed in 130 countries and over one BILLION responses registered. Most frequently, the terminals were installed at airports and retail stores, though other spaces, like sports stadiums and medical facilities, were also represented.

Why does (did?) HappyOrNot work?

I’m writing this section in the past tense because the tactile feedback terminals are part of HappyOrNot’s success, and those are obviously less desirable in the COVID and post-COVID “no touching” world.

HappyOrNot worked because it is simple. Simple for the user and simple for those analyzing the data.

From the point of the user, the terminal is simple because it removes friction from giving feedback. There’s no need to go visit a website to take a survey, fill out a comment card, or email a customer service rep. The terminal is right there, beckoning you to share what you think.

And because it’s so easy, people respond, and the data POUR in. As Väänänen noted, “If you make it easy, people will get feedback every day, even if you don’t give them a prize for doing it.”

Here’s an example. When the San Francisco 49ers installed HappyOrNot terminals at stadium entrances, bathrooms, and concessions stands, they received as many responses by the end of the first game as the number of surveys they received in the entire previous year.

But while there’s a lot of data, it’s super, super simple data. A large, structured dataset: a 4-point rating, where, when. That’s it. No customer segmentation, no follow-up questions – although the company is getting to that now with tablet offerings.

Further, most of the data’s power comes from negative responses. While the company reports that 80% of responses are positive (we’ll get to a possible reason why this number is so high below), the negative responses are the ones that bring about change.

In the case of the 49ers, if the proportion of negative responses rises at a particular terminal, the team sends out an employee to investigate the problem and then fix it. As one employee explained, “Last year, a lot of the red”—the frowny, unhappy color—“was kind of in this area, down by this end of the stadium, and now that has kind of moved over here. So we know where our problem areas are, and we can focus on those.”

So, to sum up, if you get more unhappy responses at a bathroom or at a concession stand, you look into what the problem is and then fix it. It’s not rocket science.

What’s next? Improving how we measure experience

It’s obvious that tactile button terminals are out, at least for the time being. These days, many people would avoid touching a possibly-contaminated surface, and the whole thing would quickly become slathered in hand sanitizer.

So, right now there’s no choice but to move to touchless data collection. And I think this could be a great opportunity to digitize the experience and improve on what HappyOrNot has built so far.

We’ve talked about what’s good with the HappyOrNot system—it’s simple and it’s simple. But there are two big ways it could be improved. First, reversing the backwards scale the terminals use and, second, expanding to measure more aspects of people’s experience.

Let’s address the “backwards scale” issue first. What do I mean? In the HappyOrNot universe, good (the happy green smiley) is placed on the left, while bad (the grimacing red smiley) is placed on the right.

Meanwhile, in OUR universe, there’s a natural metaphorical mapping in which good is associated with the right, and bad with the left.

Think about the following expressions in English:

Do the right thing

The right side of the law

Right-hand man

Etc. etc.

But it’s not just a thing in English-speaking countries (or in the Francophonie with its droite and gauche, or in Muslim-majority countries like Indonesia where the right hand is ‘the good hand’ and the left is ‘the hand of the devil’).

One likely explanation for the link between right and good is the fact that most of us are right-handed, and we associate positive attributes with the side of our body with which we can ably do stuff. In line with this idea, the only people who seem to associate good with left and right with bad are lefties (though both righties and lefties agree on another metaphorical mapping: up is good and down is bad). This association can change if the right-hand side of the body is no longer the more able side. Righties who suffered a stroke that impaired the right-hand side of their body and those whose right hands were temporarily impaired (by a clumsy, bulky ski glove that made it difficult to complete a fine-motor task) showed a reversal in which they associated left with good instead.

But it’s still a righties’ world out there. Which means a natural link between right and good for most of the population.

This brings us to an unanswered question: Is Heikki Väänänen left-handed? A quick review of video evidence suggests not, but if anyone knows this guy personally, let me know. Perhaps his right arm was in a cast when he devised the first HappyOrNot prototype.

I see this as the most charitable explanation for why you’d inflict a mismapped scale onto millions and millions of users while charging clients $100 per month per terminal for the privilege.

Mapping this way is not only confusing, but it also adds bias to the data. People tend to select higher ratings on otherwise identical scales when the positive attribute is on the left than when it’s on the right.

Link source. People select higher ratings when the positive attribute is on the left side of the scale.

This mismapping might help to explain HappyOrNot’s suspiciously high satisfaction ratings (80% “happy” responses across all terminals), which are considerably higher than those of other experience-rating services (e.g., 50% of reviews on Yelp are 5-stars, which has the correct mapping: more stars = right = better).

With physical terminals, the sunk costs are too high (this thing is patented after all) to switch over to a new scale.

But if we start putting digital touchless devices in spaces, the world is our oyster. Not only could we overthrow the tyranny of this mismapped scale, but we could also start measuring other aspects of experience that aren’t encapsulated in the all-important sad smiley count.

There, it’s fixed. Good is on the right, bad is on the left. Expanding the emotional range could also better capture experiences that are delightful or truly terrible.

You manage what you measure

Focusing on easy-to-quantify-and-address issues, like bad bathrooms, can lead to the experience version of teaching to the test.

After diligently measuring user dissatisfaction in bathrooms at the old LaGuardia, guess what the crowning glory of the new LaGuardia is? That’s right, bathrooms!

You manage what you measure, and if you obsess over measuring bathroom quality, then what you get are really flashy bathrooms.

The CEO of an airport terminal management company explained: “Now bathroom feedback is instant, widespread and effective, and restrooms have become key satisfaction drivers. “People say, If you can’t get the restroom right, what do I need to think about for the rest of my experience?””

The outcome? “Money is pouring into sinks and toilets, beyond those happy-face/sad-face satisfaction voting machines so many airports have installed.”

Yes, the new LaGuardia bathrooms are greige, well-lit, and reminiscent of fancy hotel bathrooms. But the last time I was there, in the long-ago year of 2019, there was one soft seating area in the entire terminal and loud announcements still played over the PA system. Addressing these kinds of issues would go a long way toward improving people’s experience, as suggested by the preponderance of soft seating in paid airport lounges and the growing silent airport trend. But if you don’t ask, you won’t know how people feel and what could improve their experience.

In many situations, it’s not enough to know people’s overall satisfaction or dissatisfaction, but also to understand their broader emotional reaction and the context.

An interesting example comes from work on measuring experience in museums. Museums have many goals that are hard to sum up with a smiley. For example, a history museum might have the goal of eliciting empathy for victims of a genocide or other atrocity. A local museum might have the goal of building a deeper emotional connection between visitors and their community.

But just because the experience is complex and multi-faceted doesn’t mean you can’t ask people how they feel about it in a way that’s easy-to-use and visual. In a fresh 2020 study, a group in the UK developed a new visual survey focused on characteristics important to museum experience that’s inspired by emoji.

The researchers developed nine emoji that corresponded to the dimensions of experience important to museum visitors – basic enjoyment (happy, sad, and angry emoji), learning (achieved emoji), overwhelmed by information (tired emoji), not engaged by what you experienced (bored emoji), inspired by what you experienced (inspired emoji), feeling involved with others (socially involved emoji), and lacking understanding (confused emoji).

Image source. Emoji developed to measure museum experience.

To check whether people could interpret the emoji they designed, the researchers asked a group of participants to type of out the first word they thought of when they saw each emoji – a method that’s been previously used to collect emoji meanings, a topic I’ve written about in detail here if you want more cool emoji content. For the most part, the emoji were clear, though people did tend to associate the tired emoji with physical, rather than mental tiredness, and the socially involved emoji with friends and love. It can be hard to convey abstract relations visually!

With a different group of participants, the researchers tested whether the emoji survey could distinguish two museum experiences they believed would differ in their quality: an augmented reality (AR) sandbox and a regular sandbox used to familiarize museum visitors with the work of a famous English landscaper.

And indeed, the visual scale worked! People who interacted with the less-engaging normal sandbox selected the bored, tired, angry, and sad emoji, while those who interacted with the cool AR sandbox did not.

What was especially interesting is that participants often chose more than one emoji to capture their experience, including emoji with opposite valence (positive vs. negative). For example, one person selected both the happy and confused emoji – the experience was positive, but they also found some parts of it confusing. This kind of response would be hidden if only a negative vs. positive scale were used.

The researchers interviewed participants to understand how they were using the visual scale. Some points might be useful to others wanting to use emoji to gather experience responses:

The confusion emoji was selected when people were frustrated with an interface, had a usability issue, or the instructions lacked clarity. It would be great to pick up on usability issues!

The boredom emoji was selected when people felt the experience wasn’t engaging or interesting. A good one to include if customer/user engagement is important.

The tired emoji was selected if people were feeling physically tired or sick. It could be a good measure to include if an experience could induce feelings of sickness – e.g., feeling motion sick in a virtual reality experience.

The socially involved emoji was selected when people thought an experience would be fun to have with friends. It could be used to pick up on solo experiences that people might want to share with others – a good prompt to send the a special offer to allow them to repeat the experience with others.

Measuring emotion

The finding that people’s emotional responses can’t be summed up with a straightforward positive or negative is in line with decades of research on emotion.

Emotion is multi-dimensional. While different dimensions have been proposed over time, three that come out time and time again when quantifying reactions to an experience are valence/pleasure, arousal, and dominance.

Valence is the difference between positive and negative, e.g., happy vs. sad.

Arousal is the strength of our physiological or psychological reaction. Someone could have a positive reaction that’s high in arousal (delight) or low in arousal (relaxed).

Dominance, or control, is the degree to which we feel we have control over the situation we’re in (vs. feeling powerless when the situation has control over us). This one is less-widely used in basic research but really useful in real-life situations where it’s important to consider how much control a user feels over their experience. It even seems to predict virality online!

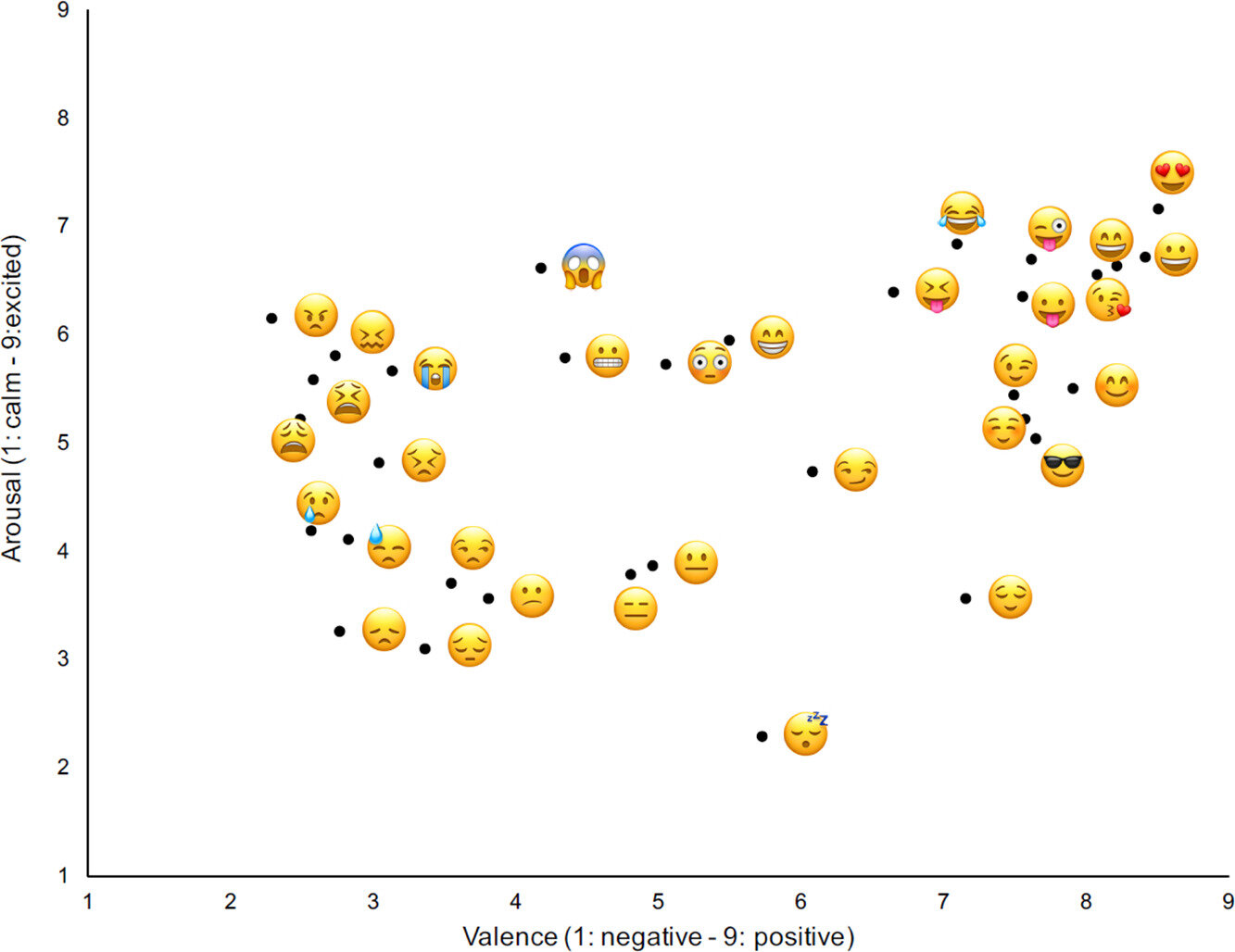

Image source. A two-dimensional representation of valence (positive vs. negative) and arousal (high vs. low).

Knowing all of this, you can begin to translate emoji to measure people’s emotional reactions.

Image source. Mapping emoji onto the dimensions of valence and arousal.

Putting it all together

Even in spaces that are less heady than museums, people’s experience is made up of many factors.

To measure them, we just need to get creative with our new touchless displays.

We could start with a larger range of emotion emoji to better understand people’s emotional reactions. For example, the emoji 😍 is much higher in arousal than 😊, so if people are selecting it, they’re probably delighted and more willing to share how great the experience is with others. Seeing what combinations of reactions people choose could also be super informative: if they select a happy emoji but also something like this 🥱, then the experience is likely not engaging enough.

We could also devise new ways to uncover what positively or negatively influences people’s experience. In an airport terminal, apart from the bathrooms, security process, and stores (areas where feedback has been collected in the past), other important experience factors that could be visualized with emoji include temperature (🥶🥵), noise (🙉🔇), accessibility (🦽), support for families (🤱🚼) and others.

Using a touchless display, we could collect feedback about what features people like and which ones need improvement by asking them to select the relevant emoji.

The time is right

It’s a good time to come up with new, creative ways of measuring people’s experience as it appears HappyOrNot is out to lunch with their current COVID pivot.

What are they up to? Well, since physical terminals are out, the company created a way for people to scan a QR code and complete the smiley survey online. While this is in step with a supposed QR renaissance, asking people to pull out their phones and scan a QR code to give feedback creates exactly the kind of friction that the physical terminals sought to eliminate in the first place!

So, the time is right for a new solution that solves the same problem, while allowing us to measure better and to measure more.