How our stuff helps us maintain who we are

I went to high school in Storrs, Connecticut, a small university town whose other claim to low-grade fame was its designation as Slate’s “America’s Best Place to Avoid Death Due to Natural Disaster”.

Apart from the avoidance of natural disaster, which was constant, the town went through large cyclical patterns of change every year. The place would empty out in May, losing as much as 55% (!) of its population. After a sleepy summer, August would bring the cars. On dorm move-in weekend, the gently winding country roads were bumper-to-bumper with New England staples – Subarus and Volvos – packed to the gills with young adults’ possessions. Laundry hampers, extra-long-twin sheets, shower caddies, framed photos, stuffed animals, books.

This year, the traditions of the dorm move-in weekend are subdued by COVID and the shift to online learning by many higher education institutions. Still, more than a third of U.S. colleges and universities plan on holding only, mostly, or some in-person classes in the 2020-2021 academic year, so the car procession continues in some university towns. The contingency plans put forward by schools vary widely, but those that have been released publicly acknowledge that certain conditions would result in campus shutdowns. And shutdowns might mean emergency evacuation. For example, Syracuse University laid out this scenario: “students may be asked to evacuate campus immediately with only those items they can carry with them. All other possessions are left behind.”

Because of the looming uncertainty of the next few months, the choice of what stuff to bring to the dorm, and what to leave at a parent’s house, might be an especially weighty one for incoming students this year.

And that is today’s topic: the stuff we bring with us when we move and how it helps us maintain a sense of self. To illustrate, I’ll focus on the experience of college students moving into dorm rooms, but toward the end will also look at other cases where this consideration is equally relevant.

Image source. Macro Sea student dorms in Berlin.

Objects are part of our extended self

We’ve briefly touched on the idea that objects, spaces, and other people can extend our minds in a previous piece on virtual environments for collaboration. Beyond extending our thinking, objects, spaces, and people can also be integrated into our sense of self.

This idea is called the extended self.

William James, the father of American psychology, said it well 130 years ago:

“Between what a man calls me and what he simply calls mine the line is difficult to draw. We feel and act about certain things that are ours very much as we feel and act about ourselves. Our fame, our children, the work of our hands, may be as dear to us as our bodies are, and arouse the same feelings and the same acts of reprisal if attacked.

…

We see then that we are dealing with a fluctuating material; the same object being sometimes treated as a part of me, at other times as simply mine, and then again as if I had nothing to do with it at all. In its widest possible sense, however, a man's Me is the sum total of all that he CAN call his, not only his body and his psychic powers, but his clothes and his house, his wife and children, his ancestors and friends, his reputation and works, his lands and horses, and yacht and bank-account. All these things give him the same emotions. If they wax and prosper, he feels triumphant; if they dwindle and die away, he feels cast down—not necessarily in the same degree for each thing, but in much the same way for all.”

James goes on to propose a hierarchy of what is likely to get integrated into our extended self: first different parts of our body, then our clothes, then our immediate family, then our home. It turns out that, as with many things, James was more or less right. For example, while body parts are the physical objects that are closest to our sense of self, within this category people believe that certain ones, like eyes and hair, are closer to the self than others, like the liver or throat.

What we integrate into our extended selves changes throughout the lifetime:

In infancy, children learn to separate the self from the environment and other people. Those items that a young child can control (e.g., a security blanket) may serve as an extension of the self more readily than items they cannot. In adolescence, possessions start to be used for self-definition, especially ones that reflect growing skills (e.g., sports gear, instruments) or that are under sole control of the adolescent (e.g., stereo, computer).

In young(er) adulthood, items that represent the future gain prominence. For example, the favorite objects of young couples living together tend to reflect their goals and plans for the future, while those of older couples tend to reflect their past shared experience. The self may reach its largest extent when people become parents. People in this middle age have past experiences and future goals, children and parents, developed skills and accumulated possessions. All of these can be integrated into an expansive extended self.

Closer to retirement, there’s a shift from defining oneself by what one does to what one has and, starting in their 40s and 50s, people may begin to use possessions as a signal of social power and status. (As an aside, when I read about this phenomenon I immediately recognized the typical demographic of people whose homes are featured in magazines like Dwell or House Beautiful). In older age, possessions that link to the past become more important. Favorite possessions of older adults often include photographs, mementos, and any possessions that symbolize others (e.g., gifts from others, handmade items).

Across life, certain categories of possessions are particularly treasured: furniture, visual art, and photos. These items are valued because they remind us of people, experiences and memories, and relationships that are important to us. And carrying these and other important possessions with us as we move over the course of our lifetime can help us maintain a coherent and continuous sense of identity when circumstances are changing.

Moving to dorms

Moving away for college or university is an important milestone for many young adults. And the dorm room is often the first place they can arrange in any way (within a set of bounds) they want to reflect their developing identity.

A recent study from Andrea Breen and colleagues explored what kind of possessions students choose to place in their dorm rooms and how these items relate to their extending sense of self.

In addition to physical spaces, there are now many digital spaces (Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, etc.) that we can also call our own. One novel aspect of this study was to examine how students used both physical and digital spaces as an extension of the self and whether these spaces serve different needs.

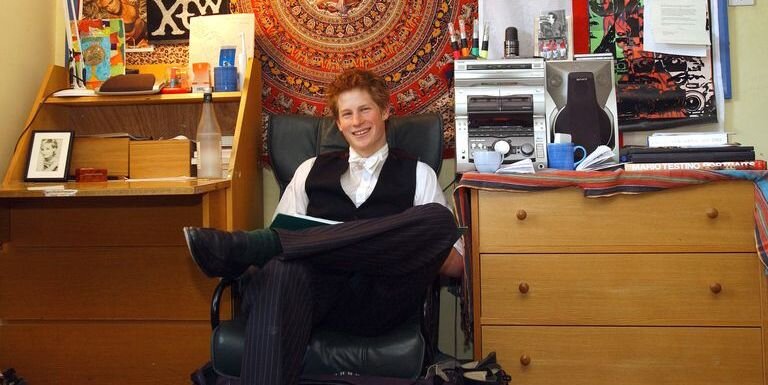

Image source. Everyone brings a little of themselves into the dorm room. Here’s Prince Harry’s: a flag, a tapestry, a picture of his mom.

When it comes to most cherished items, there was division among the students in the study: some chose to bring their most important possessions with them to the dorm, while others decided to leave them at their family home. Those who left behind their beloved items cited concerns about space constraints, fears about safety of the possessions in the dorm, or the temporary nature of dorm living – it didn’t feel like a “permanent” place to bring their items.

I wonder if the uncertainty around school closures will result in more students leaving behind beloved items at a family home this year, or at least choosing to bring only those items that can be carried by hand in case of an evacuation.

Across the board, those items that were most important to students’ sense of self shared some similar traits: they represented memories or stories about the students’ connections to their loved ones. Because they were living away from friends and family, photos and gifts represented these important relationships and allowed people to feel connected.

Other items that were important represented different aspects of the current and past self, supporting change but also a continuous identity through time. For example, two roles important to a person might be those of a sister (past, present, and future) and a student (present). Different items could represent these two important relationships. Certain items also represented ideas for future selves – e.g., a photo of someone who is an inspiration or a list of life goals.

Virtual vs. physical spaces

Students were split as to whether they believed virtual or physical spaces allowed for more personalization and a truer reflection of who they were. Some pointed out that there was almost no limit to how you could personalize an online space and that photo manipulation online allows people to “show what you want to show” in order to display idealized versions of the self. Meanwhile, others highlighted the limitations of virtual spaces, especially in only allowing for visual and auditory experience. As one participant explained:

“Facebook, yeah, it has all my photos, but it doesn’t have all the stuff that I have from my grandmother or it doesn’t have all my crazy books or my journal or my—the coat that reminds me of my dad. Like, it doesn’t have all these other things that I cannot really put on Facebook, because that’s just a medium that doesn’t allow for many things other than photos and words.”

An interesting divide between virtual and physical spaces had to do with time. And probably not in the direction that tech companies would imagine: virtual spaces were associated with the past, while physical spaces with the future.

What does that mean? Well, people felt that digital spaces tended to reflect their past selves. The photos they posted, the music they listened to, the experiences they had. Physical spaces tended to reflect their current and future selves: what activities they were currently engaged in, their current interests, their plans and goals for the future.

Something that was not explored but that I wonder about is if all digital spaces function in the same backward-looking way. While a person’s Instagram or Twitter page reflects past thoughts and experiences, I imagine something like Pinterest or the “saved” collections on Instagram might reflect ideas or future goals (e.g., I want to visit this spot, I want to cook this dish).

Students were aware of the public nature of both the physical and digital spaces they created. They were conscious that the spaces would be seen by others and made choices accordingly of the items to display to express specific identities. Items that didn’t fit these identities were excluded.

We create our physical and digital spaces for ourselves, but with a deep awareness that they are a reflection of how we will be seen by others.

Application to other spaces

Outside of dorms, there are many space types where it’s important to consider how people’s possessions might help them maintain a continuous sense of self. A few that seem especially relevant are coliving spaces, long-term Airbnb rentals, and senior care facilities.

For anyone not familiar with the term, coliving spaces are a type of communal housing where people typically rent furnished bedrooms and share furnished kitchens, living rooms, and other amenities with other renters. A big benefit is being able to move in without buying or moving furniture and having the flexibility to leave for another location without the drag of again having to move your stuff. But a possible downside is the lack of any emotional ties with possessions in your (even if it’s temporary) home. As we talked about earlier, the items that people most value in their homes are furniture, visual art, and photos. But in coliving spaces, like the large-ish chain Common, all those items are chosen by designers. The results can look great, but wouldn’t it start to feel like eternally living someone else’s life if you had no connection even to the images on the wall or the books on the bookshelf? Perhaps there are interesting ways to incorporate personalization and emotional connection into coliving spaces. Some examples could be an onboarding process that guides you to pick a few key items that remind you of important relationships (with a prepaid box sent to your family to get those items), a way to upload a few photos that would be framed and placed around your room, and space on the communal bookshelf to add your favorites.

These days, people are booking Airbnbs for longer stays. The average length stay rose during COVID – from around 3 or 4 days to around 7 or 8. While these stays are still not that, that long, some people are staying for much longer and Airbnb is pushing this option with its monthly (4+ week) stays. If someone were to stay in an Airbnb for months at a time, being surrounded by another person’s possessions might lead to a feeling of disconnection. This is especially important if people are using an Airbnb in a transition period (e.g., to escape a wildfire, to get away from COVID in the city, to move out from a relationship) and their possessions could help them maintain a coherent and continuous sense of identity in these changing circumstances. Perhaps the monthly Airbnb option could come with a special packing guide – a reminder to bring along a few items to remind guests of their important relationships, past experiences, and future goals.

Life in senior care facilities is far from normal during COVID. Facilities shut down family visits in March and many have not reopened, contributing to residents’ loneliness and isolation. As we talked about earlier, older adults highly value possessions that link to the past and represent important relationships. These types of items are very important in helping residents achieve a sense of home, but often don’t make it to residents’ rooms because of space limitations, regulations, or because the family helping with the move has no idea about the emotional importance of certain items. For any new residents moving into senior care facilities, it’s probably more important than ever to consider what objects could help them feel connected to their families in the absence of frequent visits. And though it’s a drop in the bucket compared to the time spent with family, visitors might be encouraged to bring a new item with them every visit to help visually remind the resident of the continuing relationship with family.

Our stuff is more than just stuff. Our possessions help to link us to others, represent different aspects of ourselves, and maintain a sense of self through time and circumstance.